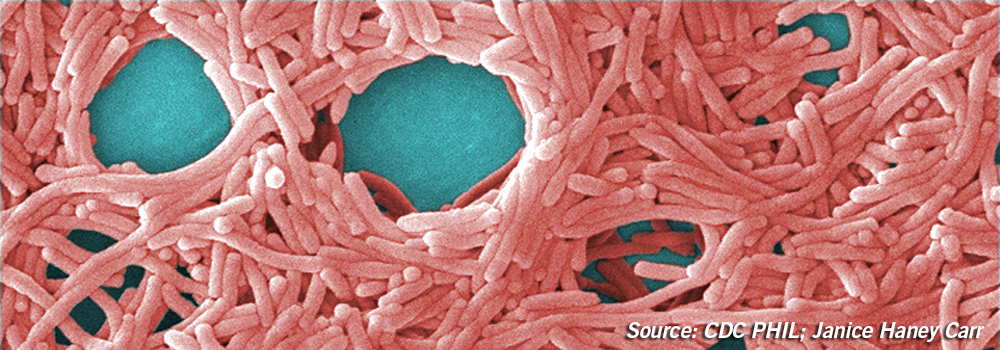

There are about 20 outbreaks of Legionnaires’ disease each year in the United States. Most outbreaks occur in buildings with large water systems such as hotels and hospitals. The outbreaks are caused by Legionella pneumophila, a harmless microorganism in a natural setting, but not so harmless when it contaminates man-made water systems.

Description: A motile, aerobic, Gram-negative rod. It is nutritionally fastidious and must be grown on an agar such as BCYE (Buffered Charcoal Yeast Extract) that contains L. cysteine and iron salts. Optimum growth occurs at 35 to 34°C and at pH 6.7 to 6.9.

Habitat: L. pneumophila is found naturally in streams and lakes. It is a facultative, intracellular parasite of several different free-living amoebae, including Acanthamoeba and Naegleria.

Legionella spp. under UV light; Source: CDC, PHIL James Gathany

Environmental Contaminant: L. pneumophila has been isolated from hot tubs, cooling towers, large plumbing systems, and decorative fountains. It prefers warm, moist environments, such as hot water heaters, where there is a supply of nutrition from the sediment. Legionella can be spread in droplets of water if it is aerosolized through a device such as a shower head. In 2011, an 82-year-old Italian woman’s death from Legionnaires’ disease was attributed to infection with Legionella bacteria from a contaminated dental unit waterline.

Pathogenicity: L. pneumophila causes legionellosis which comes in two forms: Pontiac fever and Legionnaires disease. Pontiac fever is the milder of the two diseases. Legionnaires’ disease, named for an outbreak of pneumonia in 1976 at an American Legion convention, is deadly for 1 out of 10 people who get it. Risk factors for the disease include:

- Being over the age of 50

- Being a current or former smoker

- Having a chronic lung disease

- Taking medication that weakens the immune system

Legionnaires’ disease begins with inhalation of airborne droplets containing L. pneumophila. The microorganism is taken up by pulmonary alveolar macrophages. Once inside the macrophages, Legionella multiplies intracellularly.

Detection: Two common methods of detecting Legionella in patients are the culture method and the Legionella urinary antigen test. The urinary antigen test detects Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1 which causes 95% to 98% of community-acquired Legionnaires’ disease.

Common methods of isolating Legionella from water samples include the culture method and molecular methods such as PCR. Water with low concentrations of bacteria (e.g. potable water) may be filtered and concentrated before it is tested. Swabs are used to sample faucet aerators and shower heads.

Prevention: Water systems must be well maintained in order to reduce the risk of growing and spreading Legionella. The CDC has found that outbreaks are usually caused by one or more of the following:

- Process failures such as not having a Legionella water management program

- Human error, such as a hot tub filter not being cleaned

- Equipment failure, such as a disinfection system not working

- Changes in water quality which may be caused by nearby construction

The CDC provides several guides and videos for prevention of legionellosis. Two guides are:

- Developing a Water Management Program to Reduce Legionella Growth and Spread in Buildings.

- Operating Public Hot Tubs fact sheet for pool staff/owners

- Legionnaires’ Disease: Use Water Management Programs in Buildings to Help Prevent Outbreaks (CDC Vital Signs)

Family: There are over 60 species within the Legionella genus. The species, Legionella pneumophila, belongs to

- Phylum: Proteobacteria

- Class: Gammaproteobacteria

- Order: Legionellales

- Family: Legionellaceae

- Genus: Legionella

- Species: pneumophila

Looking for Legionella pneumophila controls? Check out our website to find the right format for your lab.

References:

ADA Science in the News. (2012) Transmission of Legionnaires’ Disease Traced to Contaminated Dental Unit Waterline

CDC. Legionella (Legionnaires’Disease and Pontiac Fever) https://www.cdc.gov/legionella/water-system-maintenance.html

CDC Vital Signs. Legionnaires’ Disease. Use water management programs in buildings to help prevent outbreaks. https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/pdf/2016-06-vitalsigns.pdf

Edelstein, P. H., W. (2011). Legionella. In Manual of Clinical Microbiology (10th ed., Vol. 1, pp. 770-785). Washington, DC: ASM Press.

Winn Jr., W. C. (2005). Genus I. Legionella. In Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology (2nd ed., Vol. 2, The Proteobacteria, Part B The Gammaproteobacteria pp. 212-236). New York: Springer.

Thank you for this great article and I ‘ d like to send me what are the Up dated Biochemical Identification tests for Legionella pneumophila in diagnostic laboratories and the standard method for sample colloction??

Best regards

Dr.Khaled Kamal Hussain

These two links may help answer your questions. The first is a link to a CDC pamphlet that explains how to collect water samples for testing for Legionella: https://www.cdc.gov/legionella/health-depts/inv-tools-cluster/lab-inv-tools/procedures-manual.pdf. The second is a link to a CDC webpage that discusses topics such as Preferred Diagnostic Tests, Sensitivity and Specificity of Diagnostic Tests, and Advantages and Disadvantages for Each Diagnostic Test: https://www.cdc.gov/legionella/clinicians/diagnostic-testing.html. Good luck with your testing!